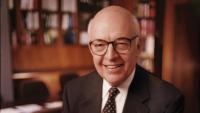

Tom Morris: A Life Well Lived

By Bonita Eaton Enochs, Editor, Columbia Medicine, 1991-2024

At the end of a solemn funeral Mass for Thomas Q. Morris’58 in the Delhi, New York, Catholic church, recorded music started playing. Smiles and chuckles rippled through the packed church as some of those in attendance recognized the tune. When the second song began, I joined them, smiling in recognition: It was the Notre Dame fight song. True Notre Dame fans recognized the first song as “Notre Dame, Our Mother.” The second song, universally known by even non-football fans like me, was “Notre Dame Victory March.”

I knew Dr. Morris—TQM to many—for 24 years, 21 years of which he served as chair of the editorial board of this magazine. His love of Notre Dame football was widely known, and he told me of frequent trips to South Bend each fall for games. At his wife’s funeral Mass in 2021, he said one of the many lessons his wife of 62 years taught their children was this: “Stay away from Dad on Saturday afternoons in the fall. He’s watching Notre Dame football, and he thinks it’s important.” She eventually understood the importance, he continued, and joined him in rooting for the Fighting Irish on trips to Indiana each fall. Dr. Morris would have been thrilled with the Fighting Irish wins following his death on Dec. 28, including their Orange Bowl victory and berth in the national championship game.

His passion for Notre Dame, his undergraduate alma mater, was matched only by his passion for medical education and P&S, his medical school alma mater. His ties to Notre Dame could be traced to his college years and, yes, his passion for the Fighting Irish, but his ties to Columbia involved much more than his MD degree, earned in 1958, and his training.

As a physician and medical school administrator and in his roles on hospital and non-profit boards, he focused on education, whether through direct mentoring, curriculum development, the Columbia-Bassett Program, or scholarship support. His four-year role as acting chair of medicine coincided with the emergence of HIV and AIDS, but his enduring memory of that time, according to an interview for a Columbia publication, was helping students and residents progress. It fell upon him, as department head, to support his residents in dealing with their concerns about caring for patients with a uniformly fatal disease caused by an unknown infectious agent.

I met Dr. Morris near the end of his active career, just a few years before he “retired.” He was interim dean for clinical and educational affairs when he stepped in to chair the editorial board following the death of Donald Tapley. Despite his busy schedule as interim dean, he attended editorial board meetings and made time to review each magazine issue’s manuscript and layout, offering suggestions along the way. He retired from P&S in 2003, ending the many formal roles he held throughout his 50 years at Columbia: medical student, chief resident, acting chair of the Department of Medicine, president and CEO of Presbyterian Hospital (the openings of the Milstein Hospital Building on the medical center campus and Allen Hospital in Upper Manhattan were among the highlights of his tenure), and many other roles in between.

His retirement to Delaware County in upstate New York may have included some of the country life he envisioned (tending to a vegetable garden and building stone walls), but the 21 years after his retirement were also defined by service and advocacy: member (and frequently chair) of boards for the American University of Beirut, the New York Academy of Medicine, the Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital, Presbyterian Hospital, Morris-Jumel Mansion, and multiple foundations—plus all the travel those responsibilities entailed. As he left on trips, he said in an alumni reunion questionnaire, his wife would tell him, “Remember, you’re retired.”

His retirement was anything but typical. Perhaps that’s why in his last email to me, he told me to enjoy my own “retirement” (his quote marks). Per his example, retirement was more a second act than a slowing down.

Dr. Morris and I exchanged Christmas cards each year. My card was usually a family photo or a photo of my three children, whose educational journeys he asked about frequently. His card typically was a photo of his Delhi home, Jaminnjelly Farm. His last card, from 2023, featured a photo of a rainbow over Jaminnjelly. Inside he wrote, in his familiar tiny script handwriting, “Hope 2024 will be all you hope for—with a rainbow or two.”

He knew I planned to retire in 2024, so I interpreted his use of “rainbow” as a metaphor for my plans and maybe other good things. And, indeed, 2024 did have many “rainbows” for me, from my children’s successes to my own retirement festivities. I also enjoyed a literal rainbow when my husband and I went to a farm in Nebraska to dog-sit for three weeks following my retirement. We captured a photo of the rainbow over the farm following an early morning rain shortly after we arrived, and I sent it to Dr. Morris in a text along with a photo of the dog we were caring for. (During one of my last visits with him, he explained how his dog, Liam, got his name. The dog had joined the family with the name William, but because Dr. Morris’ father and brother were named William, the dog’s name was changed to Liam.)

Less than two weeks after my retirement party, I visited him in the hospital the night before his brain surgery for a glioblastoma that was discovered after a fall at his home in Delhi. We talked about Notre Dame football and the games he would miss because of his health. We discussed the fighting in Lebanon and his concern about the impact on the American University of Beirut, for which he served on the board for 24 years and visited several times a year while a board member. His concern included the well-being of the school’s president, fellow P&S graduate Fadlo Khuri’89. He told me about a visit during the summer by three women who had been residents at NewYork-Presbyterian during Dr. Morris’ time as acting chair of medicine. The women called him and said they were coming to Delhi for a mini reunion. He proudly said the women noted that he never raised his voice during their training. Clearly, the mini reunion was one of his 2024 “rainbows.”

Even though Dr. Morris and I stopped working together formally after he stepped down as chair of the magazine’s editorial board, he remained active as a board member and was engaged in our meetings. Leading up to my retirement, he helped me workshop a farewell essay for my final issue, and he traveled to New York City in September to give remarks at my retirement party.

People who knew and worked with Dr. Morris often mention his humility. At the January funeral service, Dr. Morris’ son mentioned that trait in his eulogy: “He accomplished so much,” said the son, also named Tom, “and touched so many lives. And yet we all know he would not want the conversation to be about him. His humility was a central thread that emerged in many of the notes and tributes that have been written.”

His sense of humor often reflected this humility. At my retirement party, he was introduced by Lisa Mellman, MD, current chair of the magazine’s editorial board. She listed his many roles at Columbia, from his 1954 enrollment as a medical student, through training, through 11 medical school administrative roles, hospital appointments and leadership roles, and his service beyond the campus until his ultimate appointment as Alumni Professor of Clinical Medicine. When Dr. Morris reached the podium, he quipped, “If my wife were here and heard that, she would say, ‘He just couldn’t hold a steady job.’”

Phrases that come up when people describe TQM include these: true gentleman, humble, generous, supportive, and wise. As Linda Lewis, MD, who worked with Dr. Morris while senior associate dean for student affairs, put it: “Most important was the example he set: even keel, good humor, tolerance, vision, making us all better at personal and professional levels, and encouragement.”

Many others at VP&S and throughout Columbia knew Dr. Morris longer and better and in different ways than I did, and this remembrance cannot do justice to his extraordinary contributions to the University and to medical education. But my look back at his career leads me to believe that by working in so many roles throughout Columbia and the hospital, Dr. Morris left a legacy that is felt across department, school, and campus boundaries.

Remembering him also leads me to believe that all of us who were beneficiaries of any aspect of his legacy should be grateful that he “couldn’t hold a steady job.”